The world of lab-grown diamonds has revolutionized the jewelry industry, offering consumers an ethical, sustainable, and often more affordable alternative to mined stones. At the heart of this technological marvel are two primary methods of creation: Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) and High Pressure High Temperature (HPHT). While both produce genuine diamonds—chemically, physically, and optically identical to their natural counterparts—the paths they take to achieve this result are vastly different. Understanding the nuances between these processes is crucial for anyone looking to make an informed purchase, as the method of creation can influence the diamond's characteristics, quality, and even its final cost.

The HPHT method is the elder statesman of lab-grown diamond technology, first successfully replicating nature's process in the 1950s. This technique seeks to mimic the extreme conditions deep within the Earth's mantle where natural diamonds are formed over billions of years. The process involves placing a small diamond seed, often a sliver of a natural diamond, into a specialized press. This press subjects the seed to immense pressures exceeding 1.5 million pounds per square inch and scorching temperatures that can reach over 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit. Within this controlled environment, a carbon source, typically graphite, melts and dissolves onto the cooler diamond seed, allowing a new diamond crystal to slowly form layer by layer.

The resulting HPHT diamonds are known for their robust crystal structure. They often exhibit exceptional clarity and can produce stunning white diamonds of high quality. However, the process is not without its quirks. The metallic catalyst used inside the press can sometimes leave minute metallic inclusions within the diamond. Furthermore, the extreme conditions can impart certain color characteristics. HPHT is particularly renowned for its ability to produce fancy colored diamonds, especially blues and yellows, with remarkable efficiency and vibrancy. The process is also highly effective at correcting color in other diamonds, making it a common method for post-growth treatment to enhance whiteness.

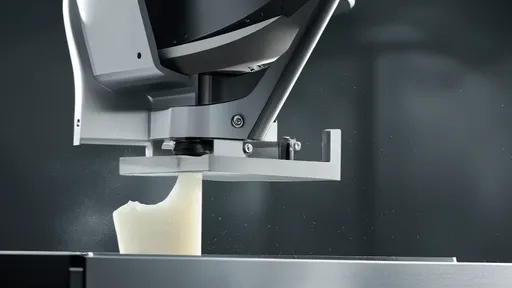

In contrast, the CVD method represents a more modern, space-age approach to diamond synthesis. Developed later than HPHT, CVD foregoes the crushing pressures and instead relies on sophisticated chemical reactions that occur in a vacuum. The process begins by placing a diamond seed plate, typically a thin slice of an HPHT-grown diamond, inside a sealed chamber. This chamber is then filled with carbon-rich gases, most commonly methane, and heated to temperatures around 1,400 to 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit. Energy, usually in the form of microwaves, is introduced to ionize the gas, breaking down its molecular bonds and freeing carbon atoms.

These liberated carbon atoms rain down onto the diamond seed plate, where they meticulously arrange themselves into the crystal lattice structure of a diamond. It is a painstakingly slow process of atomic layering, akin to 3D printing at a molecular level. One of the most significant advantages of CVD is its exceptional control over the growing environment. This precision often results in diamonds with very high purity and fewer inclusions, particularly the metallic ones sometimes found in HPHT stones. CVD diamonds frequently achieve high clarity grades and can grow with very neutral color, sometimes even reaching the coveted D-color grade without the need for post-growth treatment.

When examining the visual outcome, subtle differences can sometimes be discerned by expert gemologists. HPHT diamonds, due to their growth conditions, can exhibit a slightly different strain pattern under cross-polarized light and may have a distinctive cuboctahedral shape. Their color can sometimes have a faint blue or yellow hue depending on the impurities present. CVD diamonds, growing layer by layer, can occasionally show striations or a faint brownish undertone if not grown under optimal conditions, though this is often removed through subsequent HPHT annealing. The vast majority of stones from both methods, however, are indistinguishable from each other and from natural diamonds to the naked eye.

The question of which method is superior is not a simple one to answer, as it largely depends on the desired outcome and application. For jewelry enthusiasts seeking a brilliant white diamond, a high-quality stone from either process is an excellent choice. CVD might have a slight edge in achieving the purest whites without treatment, while HPHT excels in creating consistent and vibrant fancy colors. For industrial applications, where durability and thermal conductivity are paramount, the method is chosen based on which can most efficiently produce the required crystal type and size.

From a consumer perspective, the most important factors remain the Four Cs: Cut, Color, Clarity, and Carat weight. The growth method is simply a backstory. Reputable jewelers and grading laboratories like the GIA and IGI treat lab-grown diamonds with the same rigorous standards as mined diamonds, grading them on the same scales. A well-cut VVS1 clarity, D-color diamond will dazzle regardless of whether it was born from immense pressure or a plasma cloud. The certification report is the ultimate arbiter of quality, not the production technique.

Ultimately, the choice between a CVD and an HPHT lab-grown diamond is less about picking a winner and more about understanding the marvel of human ingenuity. Both methods are testaments to our ability to harness extreme science to create beauty. They offer a sustainable choice without compromise, providing all the fire, brilliance, and durability of a mined diamond. As the technology continues to advance, the lines between these methods may blur even further, leading to an even higher standard of quality and availability for consumers around the world.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025