As global demand for sustainable resources intensifies, algae cultivation has emerged as a promising frontier in biotechnology, agriculture, and renewable energy. The method of cultivation, however, remains a subject of intense debate and strategic consideration. Two primary systems dominate the landscape: the traditional open pond and the more technologically advanced photobioreactor. Each presents a unique set of advantages and profound challenges, shaping the economic and ecological viability of algae-based ventures.

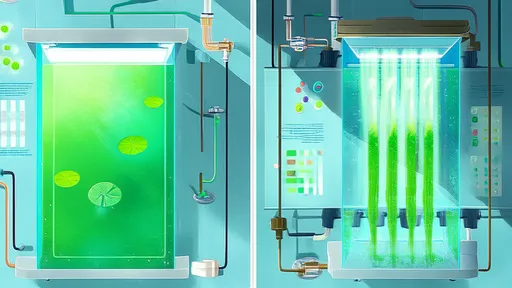

The open pond system, often resembling large, shallow raceways, is the older and more widely implemented method. Its most significant allure is its comparatively low capital expenditure. The construction is straightforward, typically involving earthworks and lining to create a shallow basin where water, nutrients, and algal cultures are mixed and circulated with paddlewheels. This simplicity translates to scalability; vast areas of land can be converted into production facilities without the prohibitive costs associated with complex machinery. For large-volume, low-value products like certain biofuels or animal feed, the open pond's economic argument is compelling. Furthermore, operating these systems can be less energy-intensive, primarily requiring power for circulation and nutrient mixing, rather than for the sophisticated environmental control needed in closed systems.

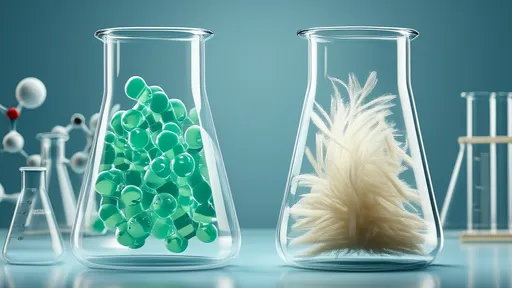

However, the very openness that makes these ponds affordable is also their greatest Achilles' heel. They are profoundly vulnerable to contamination. Open to the elements, they are a welcoming environment for invasive algal species, bacteria, and predatory zooplankton, all of which can outcompete or consume the desired culture, leading to catastrophic crop failures. This vulnerability necessitates the use of highly resilient, often extremophilic, algal strains that can thrive in harsh conditions (e.g., high salinity or pH) that discourage invaders, severely limiting the biological diversity that can be cultivated. Another critical drawback is the lack of environmental control. Productivity is entirely at the mercy of the weather—temperature fluctuations, rainfall, and evaporation all disrupt the delicate balance of the culture medium. Perhaps most frustrating is the limitation of light penetration; in dense cultures, cells shade each other, drastically reducing the overall photosynthetic efficiency and biomass yield per unit area.

In stark contrast, photobioreactors (PBRs) represent a paradigm of controlled environment agriculture. These closed systems, which can be tubular, flat-panel, or columnar in design, are engineered to optimize every aspect of algal growth. The most celebrated advantage is the precise control over cultivation parameters. Scientists can meticulously regulate temperature, pH, nutrient dosage, and gas exchange (CO2 and O2), creating an ideal and consistent environment for a wide variety of fastidious algal species, including those engineered for high-value pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and cosmetics. This control directly tackles the contamination issue; by being a sealed system, PBRs effectively exclude foreign organisms, allowing for monoseptic (pure) cultivation over long periods.

A key technological triumph of the photobioreactor is its enhanced light utilization efficiency. Designs often incorporate methods to expose cells to light more effectively, such as through turbulent flow in glass or plastic tubes that constantly move cells between the light-rich exterior and the darker interior of the culture. This reduces shading and can lead to vastly higher biomass densities and productivity rates per volume than achievable in any open system. This high productivity on a small land footprint is a major advantage for operations space-constrained or those aiming for a high-output facility.

Yet, this advanced control and productivity come at a steep price. The capital and operational costs of photobioreactors are significantly higher. The construction involves expensive materials like transparent plastics, glass, pumps, sensors, and control systems. The energy requirements are also substantial, needed for pumping, cooling (to combat heat buildup from lights and sunlight), and maintaining sterility. These economic factors often confine PBR use to the production of high-value compounds where the return on investment justifies the initial and ongoing expenses. Scaling up PBR systems presents its own set of complex engineering challenges, involving fluid dynamics, gas transfer rates, and material durability, making massive, hectare-scale PBR facilities a formidable and costly endeavor.

The choice between these two systems is rarely clear-cut and is fundamentally dictated by the end product. For commodities where cost per kilogram is the paramount factor, the open pond, despite its lower efficiency and higher risks, often remains the only economically feasible option. The strategy involves managing its inherent risks through robust species selection and large-scale operation to absorb occasional losses. Conversely, for specialty chemicals, human nutritional supplements, or research applications where purity, consistency, and high concentration of specific metabolites are required, the photobioreactor is indispensable. Its ability to deliver a clean, reliable, and potent product outweighs its economic drawbacks.

Looking forward, the industry may not see a outright winner but rather a trend towards integration and hybridization. Some operations begin growth in the controlled, sterile environment of a PBR to establish a robust culture before transferring it to an open pond for bulk growth, attempting to leverage the strengths of both. Continuous technological innovations aim to reduce the cost of photobioreactors through cheaper materials and more efficient designs, while biological research strives to develop more robust and productive strains for open ponds. The ultimate path forward lies in aligning the cultivation technology with the specific biological, economic, and environmental goals of the enterprise, ensuring that algae can truly fulfill its potential as a sustainable resource for the future.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025