The landscape of sustainable packaging is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by an urgent global push to reduce plastic pollution. Among the frontrunners in this green revolution are two distinct classes of materials: Polylactic Acid (PLA), a bioplastic derived from plant sugars, and various forms of cellulose-based materials, often sourced from wood pulp or agricultural waste. While both promise a greener alternative to conventional plastics, their performance characteristics, environmental footprints, and practical applications paint a complex and nuanced picture for manufacturers, brands, and consumers alike.

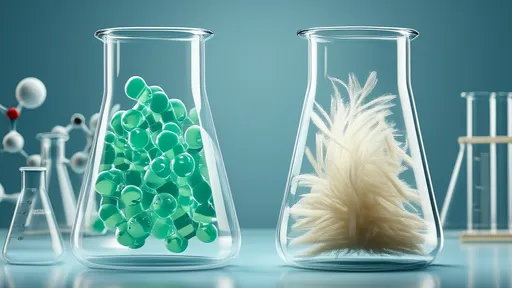

Polylactic Acid, commonly known as PLA, is a polyester synthesized through the fermentation of carbohydrates from crops like corn, cassava, or sugarcane. The process involves extracting dextrose, fermenting it into lactic acid, and then polymerizing it to create a versatile plastic. Its most significant advantage lies in its manufacturability. PLA can be processed on standard plastic equipment designed for conventional polymers, making it a relatively easy drop-in solution for many existing production lines. It offers excellent clarity and gloss, rivaling that of polystyrene or PET, which makes it highly attractive for transparent packaging applications where product visibility is key. Furthermore, it provides good rigidity and printability, allowing for high-quality branding and labeling.

However, the performance of PLA is not without its compromises. Perhaps its most notable limitation is its thermal sensitivity. PLA has a relatively low glass transition temperature, typically around 55-60°C. This means that items packaged in PLA can soften or deform in hot environments, such as a car on a sunny day or in warm storage conditions, rendering it unsuitable for hot-fill applications or products requiring sterilization. Its barrier properties, particularly against moisture and oxygen, are also moderate. While sufficient for short-shelf-life dry goods, these properties are often inadequate for protecting moisture-sensitive or oxygen-prone products over extended periods without additional coatings or multi-layer structures, which can complicate its end-of-life disposal.

On the other side of the ring are cellulose-based materials. This category is broad, encompassing everything from regenerated cellulose film (often known by the trade name Cellophane, though it is now typically coated with a biodegradable layer) to newer composites and papers with high cellulose content. The fundamental building block, cellulose, is the most abundant organic polymer on Earth, found in the cell walls of plants. Materials derived from it boast a compelling environmental narrative, especially when sourced from sustainably managed forests or agricultural by-products. They are inherently biodegradable and compostable in a wide range of environments, including home compost heaps, often breaking down much more readily and completely than many bioplastics.

In terms of performance, cellulose materials excel in their barrier properties. They offer an exceptional barrier to air, oils, and greases, which is why they have been a historical favorite for food items like candy, baked goods, and snacks. This natural barrier helps to preserve freshness and prevent rancidity. However, a fundamental weakness of pure cellulose is its permeability to water vapor. An uncoated cellulose film will easily allow moisture to pass through, which can lead to products becoming stale or soggy. To combat this, many cellulose-based packaging solutions are coated with thin layers of other biodegradable polymers (like PLA or PHA) to enhance their moisture barrier while maintaining overall compostability.

When comparing the two, the choice often boils down to a trade-off between functionality and environmental idealism. PLA presents a high-performance material that mimics conventional plastic in look and feel, making the transition easier for consumers and industries. Its weakness is its industrial composting requirement for timely breakdown; in a home compost or natural environment, it can persist for a long time. Cellulose materials, by contrast, feel more "natural" and offer superior biodegradation, but they can struggle to match the durability, clarity, and moisture resistance of PLA without additional coatings or lamination, which adds complexity.

The end-of-life scenario is perhaps the most critical differentiator. PLA is designed to biodegrade, but efficiently only under the specific conditions found in industrial composting facilities—high temperatures and controlled humidity. Without access to such facilities, PLA may not degrade much faster than conventional plastic in a landfill or the ocean, leading to potential greenwashing concerns. Cellulose materials, particularly uncoated ones, typically biodegrade effectively in a much wider range of environments, including soil, marine water, and home compost bins, aligning more closely with a circular economy model where waste is returned to the earth as nutrient.

Ultimately, the competition between PLA and cellulose is not a battle with a single winner. The sustainable packaging landscape is vast and requires a diverse toolkit. PLA stands as a robust, versatile bioplastic ideal for applications requiring clarity, stiffness, and a moderate barrier, where industrial composting infrastructure exists. Cellulose-based materials offer a more universally biodegradable solution, excellent for dry goods and products requiring a strong aroma or grease barrier, championing a return to a more natural material cycle. The future likely lies not in choosing one over the other, but in innovating within both fields—developing heat-resistant PLA blends and enhancing the moisture barrier of cellulose composites—and, most importantly, in building the waste management infrastructure to ensure these promising materials fulfill their environmental destiny.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025